One of the paintings in “The Complicit Eye” at Taller Puertorriqueño, a Latino cultural center in North Philadelphia, features a European figure dressed in radiant finery. He is a serene archangel, the kind you see in a lot of medieval art. He is carrying a sword. Below him is a naked, brown-skinned woman with no head. The freshly-severed head, held by the hair, is hanging from the archangel’s left hand. It’s open-eyed, looking directly at you, the viewer, with an accusatory expression. It’s a self-portrait.

“Each of these paintings are a slice of the complexity of my life, which are the same as any other life,” said Kukuli Velarde. “We have so many experiences as we go through life. I just make mine into paintings.”

“The Complicit Eye” is a retrospective going back 14 years. That’s when Velarde started painting what she calls “Cadavers,” after a joke to a friend that painting is dead. The portraits riff off of classic masterworks, comics and pop art, and mixed-media work deeply rooted in her Peruvian heritage.

She puts her naked self into Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus,” but awkwardly, trying to shoehorn an average Peruvian body into the mold of an idealized Western goddess. She painted an image of the Madonna cradling the dead Jesus Christ, a la the Pieta by Michelangelo – but both Mary and Jesus are her.

She painted herself being burned at the stake. Mutilated, her body is riddled with arrows, her eyes gauged out, her tongue and breasts cut off.

“Peru and Latin America are very Christian – Catholic particularly. We grew up looking at the saints and Jesus Christ images that are bleeding, and beautiful, and bleeding, and suffering,” said Velarde. “It makes you wonder why suffering is so venerated. Women who suffer a lot are good women.”

Most of her work tends to be rooted in the cultural overlap of the native indigenous people of Peru and the conquering Spanish colonialists of the 16th century. That friction is matched by Velarde’s own experience navigating the modern world as a feminist, immigrant, mother, and artist.

Velarde grew up in Peru, where she was a child prodigy. She had her first gallery show at 10 years old, and regularly appeared on TV and radio in Peru for 15 years. By the time she was 24 she was popular and successful. Then she left Peru for America.

“I wanted to look for what it means to be an artist away from my parents and their almost fanatic support. My father thought I was the best artist in the world,” she said. “I left Peru because I was young and my parents were very restrictive. My father thought of me as somebody who could create within four walls.”

“Freedom,” she said, “is very intoxicating.”

That was 30 years ago. Velarde eventually settled in Philadelphia and has won major awards for her work, including Pew and Guggenheim Fellowships, and shown work. She has had solo exhibitions in galleries across America and in Peru. Until now has never had a large show in Philadelphia.

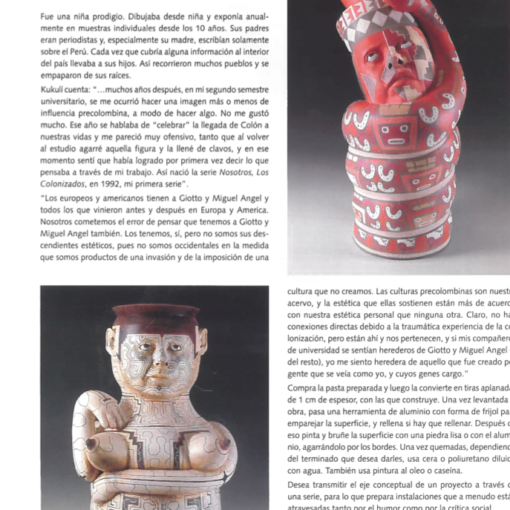

She has become known for her ceramic work, playing with pre-Columbian Peruvian sculptural forms to express modern sensibilities. None of that is in “The Complicit Eye,” a retrospective carefully tailored to the self-portraiture of the last 14 years, which has a remarkably consistent through-line.

In 1992, while a student at Hunter College, she wrote a poem, excerpted here:

If I play the game, woman and Latina

here in New York,

nice and quiet,

harmless and obedient,

subordinate and ignorant,

I can consider myself a free individual.

She recently rediscovered that poem — it is presented at the door of the exhibition hall — and realized she hasn’t changed much in a quarter century. The struggle with complicity and freedom, toggling between suffering and humor, runs through her work. She rails against popular standards of beauty in the Venus picture and in a portrait where she paints herself as a 1940’s pinup girl but with taped-on correctives, semi-transparent Mylar layers tracing where her breasts should be fuller and her legs longer.

“You are taught all the time in the shopping mall, catalogues and advertising — you are reminded that you are not that paradigm of beauty,” she said.

When Velarde talks about “A Mi Vida,” a nude portrait of herself nine months pregnant with Vida, her daughter, she suggests that she has not freed herself from that beauty myth, but holds it at arms length.

“When I was 48 and got pregnant, for a moment I felt I could escape the male gaze and see my beauty,” she said. “Three days before I gave birth I believed I was the most beautiful I had ever been in my life.”

The show features her most recent work, perhaps representing a new direction: “Daddy Likee?,” a tapestry painted on bark. Her reclining nude figure is resting on bands of patterns based on a traditional Peruvian woven wrap used by indigenous women for special occasions.

Traditionally, the weaving would include tocapus, patterns of ancient Incan pictographs of shapes and figures. “It’s not known exactly what they mean,” said Velarde.

Instead, she makes patterns devised from images of her own past work, including many pieces in this show. The language she paints is her own lived mythology.

“I don’t want to be copying or reproducing something that doesn’t mean anything to me,” she said. “They are my heritage, but I cannot take them irresponsibly. I cannot use tocapus because I don’t know what tocapus mean.